Burgess is a writer so sympathetic, for me, one for whom I feel such a strong affinity and in whom such comfort, that I am surprised every time I read a passage, even one I’ve read tens of times before. How can such excellence seem so effortless? The facility of language is one thing: the endless onion-layered sentences, with pointed detail but unfussy cadence - in short the wit of it. But there are other witty writers at whom, though I love them, I marvel in hushed reverence: Joyce, Rushdie, Foster-Wallace etc (writers in whose words one can hear the work). His overflowing font of history and place is another: he can make a meeting with Goebbels seem a camp anecdote and the lighting of a cigarette a lesson in sociology. But again in that he has peers.

Maybe it’s this: there are writers who wear their genius so heavily their heads tip back under its weight. With Burgess we’re in on it somehow. You could have a Tiger beer with him in Imperial Malaysia, or share a catty little comment in a 30s cabaret. The sweep of 20th Century history, with all its cruel detail, becomes a mosaic in which brightly coloured tiles are allowed to balance the muted. The absurdity of it all is a joke Burgess shares with us; he never pronounces from on high. I feel this about other artists: I worship Beethoven and Mahler but they are ascended beings. Brahms and Dvorak would stand their rounds and suggest another.

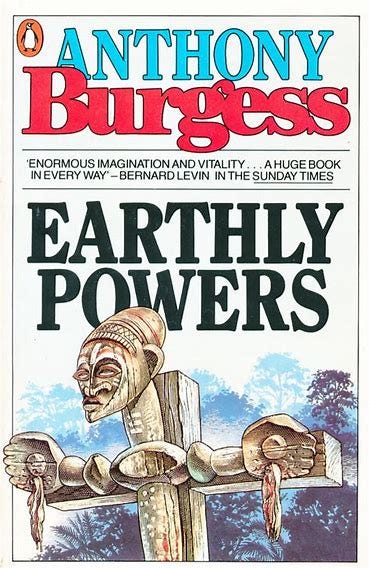

Earthly Powers - Burgess’s 1980 masterpiece - begins in an outrageous key: ‘It was the afternoon of my eighty-first birthday, and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me.’ Kenneth Toomey, allegedly based on Somerset Maugham, is the 81-year-old . The novel parodies the modern blockbuster novel, divided into 82 chapters, each chronicling a different experience in his long, history-hugging life.

That opening note is fruity, litotic and striking: knowing what one does of Burgess’s interests, he will have thrilled at the etymology more than the provocation of that word catamite. Its comic content comes not from its meaning, as such, but from its linguistic…well, silliness. The comic potential of language is something Burgess explores throughout his work but points so often to a love of the continental, the capital C Catholic, the grand, the camp. No Tolkien he, still less Hemingway. What Martin Amis called his “garlicky puns” point at this sun-kissed civility. He was a jack of all trades (if a master of some too) and was in particular a musician. And a real lover of language.

That may well be why I love Earthly Powers quite so much: I want grand words, I want the allure of the ancient, the Med and the dawn coming up like thunder out of China. I want to know what brands of gin a 1950s snob of the genre patronised. I want to feel that it’s all absurd but sweepingly beautiful for it.

I will hope for that facility of language. I will hope for all that historical knowledge. I will hope to keep a wry, raised eyebrow. And I will hope for excitement on my eighty-first birthday.

Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess. I love it.