Last year, rum-sodden and sunburnt, I was staggering along a dark path in the garden of a hotel on St. Lucia. There were lights in the distance, flickering through trembling palm leaves. To see where I was going I put on the torch on my phone: there then glimmered into life the strange, protruding black eyes and diaphanous skin of a whole troupe of tropical cane toads. Pure placidity: they sat there in the dark, staring straight ahead, the odd ribbit here and there. Old as mountains. I gave them a nod and went drunkenly on my way. They’re still there I’m sure.

I think frogs are fun: they look silly but friendly, and yet they just plod around, minding their own business, happily existing in the world. Of course, some are fantastically poisonous; exudations from the skin of the golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis: great name) are traditionally used by native Colombians to poison the darts they use for hunting. The “Phantasmal Poison Frog” (pictured below) excretes a painkiller 200 times more potent than morphine. Now we’re talking.

Frogs so often play hapless or comedic roles: think of Mr. Toad in the Wind in the Willows or Kermit, the most famous frog in history. Even in Ancient Greece, frogs can be figures of fun. The Batrachamyomachia (the frog-mouse war) is a mock epic attributed to Homer himself, but parodying his Iliad, in which an unfortunate pond-crossing leads to a one-day war between mice and frogs, which comes to an end only when Zeus sends in a crack troop of armoured….crabs. In Aristophanes’s The Frogs, the God Dionysos engages, on his voyage across the underworld, in a mock debate with a group of frogs who, in possibly the world’s first bioacoustic onomatopoeia, famously contribute this: “Brekekekèx-koàx-koáx” Perhaps slightly more accurate that the humble English frog’s ribbit.

In perhaps the most famous poem in Japanese literature, the frog gets a slightly more rarified treatment:

古池や 蛙飛び込む 水の音

The old pond -

A frog leaps in:

the sound of water.

The Old Pond, by Matsuo Basho.

Traditional haiku have “kigo” or season words. These are literary allusions that imply the season: frog, in this case, implies spring (which is particularly attractive since, in English, frogs are literally as well as metaphorically springy). In Japanese, the word for frog - kaeru - is a homophone with the word for change. And thus the spring connection is both figurative and botanical.

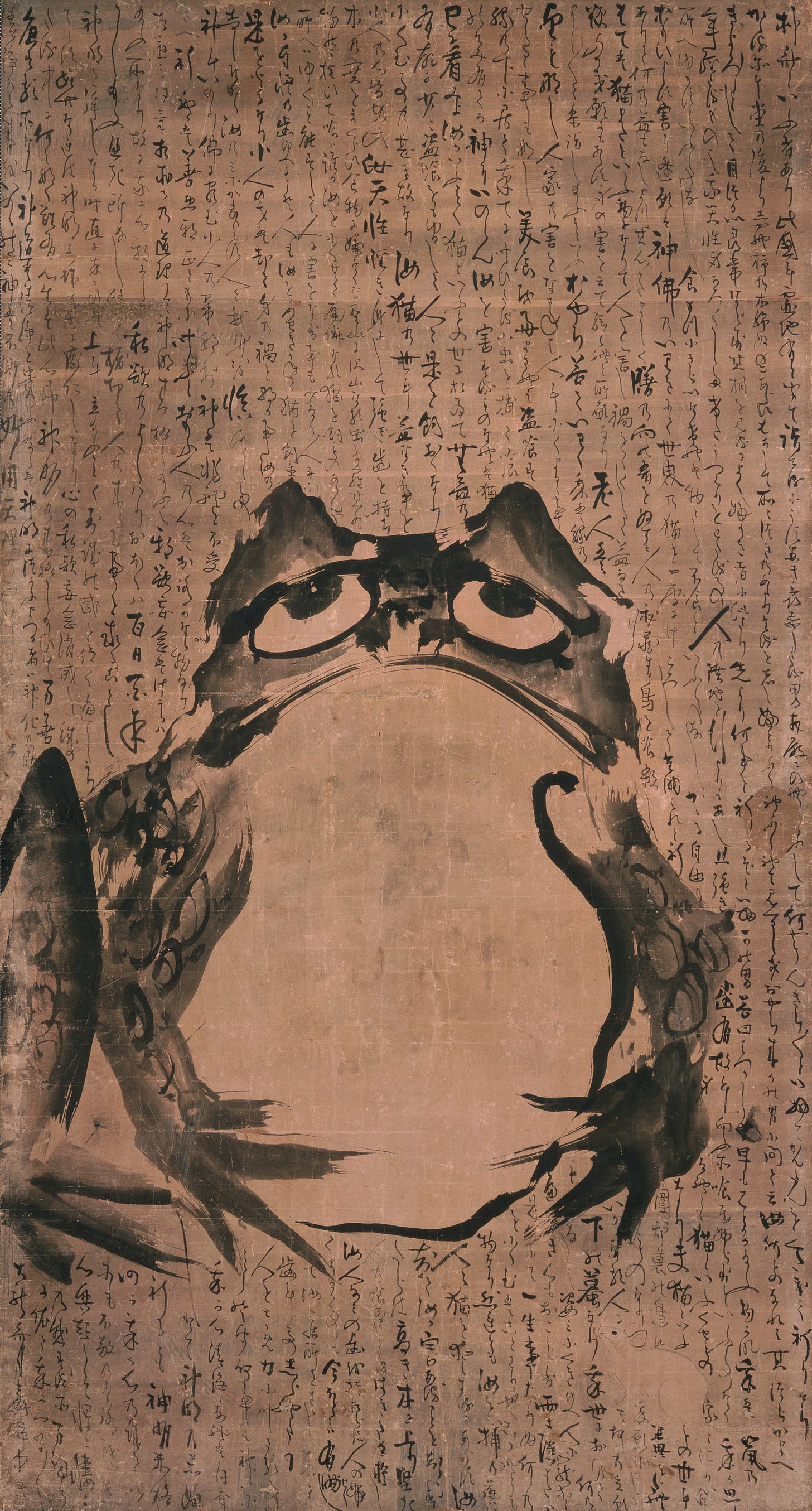

Even in Asia, though, the frog has a comedic side. Here is another frog haiku by another haiku master, Buson:

月の句を 吐いてへらさん 蟇の腹

let me spit out

moon poems to relieve the belly

of this toad

Buson here refers to a Chinese legend, where a bullfrog lives on the moon and devours it to cause the lunar eclipse. But when the frog has eaten too much, its belly begins to swell. And, sake-filled, Buson has eaten too much while watching the full moon. I suspect a lick of the Phantasmal Poison Frog would do a significantly better job of dealing with that discomfort.

Ribbit.

Frogs. I love frogs.