Bashō is the earliest of the four great Japanese haiku masters. Except he never wrote a haiku in his life. Or rather, he would never have called his verse haiku.

It’s a curious poetic form with a curious genesis. As Japanese culture matured and asserted itself, artists gradually removed the silk gowns of all-preponderant Chinese culture in which they had been dressed. Like Britain, I suppose, Japan - an archipelago ranged across the sea from a dominant, continental culture - had imported most if not all of its fine culture. Into the second millennium AD, poetry was composed primarily in Chinese and almost always in Chinese forms.

In the sixteenth century, Bashō’s era, it became popular to have boozy poetry parties at which attendees would riff of each other’s verse to produce their own. This being Japan, there were strict(ish) rules about the content of each of the links in the verse chain and it became common, if you were having a shindig, to invite a professional poet-cum-umpire to guide proceedings and to start things off. Enter Bashō.

The first verse in the chain - which was called a hokku - set the tone for the rest of the piece but was also required to anchor the poem in a time and place. One of the great devices in Japanese literature is subtle allusion, often layered on other allusion; the great skill in hokku setting was to hint at the gathering or its host and, crucially, to evoke the season in which the gathering was taking place. After the 5-7-5 hokku comes a 7-7 response. Then 5-7-5, 7-7, and so on.

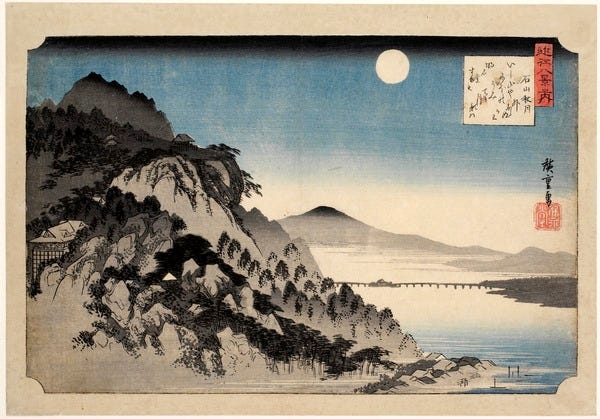

It is from hokku that haiku were born: lines of 5-7-5 with a seasonal reference. Short but capable of inducing breathlessness. A flashing, sharp connection to nature. An image for meditation.

It's not like anything

they compare it to -

the summer moon

First winter rain -

even the monkey

seems to want a raincoat.

How admirable!

to see lightning and not think

how fleeting life is

There’s no gloss with these poems. There’s no rhyme or metre. Nothing epic. Nothing conceited. Just a single thought and the world that thought was conceived in. There’s something lonely about it, perhaps. Or stoical. When they’re beautiful, they’re not like anything they compare them to.

They’re fun and easy to write yourself. My Japanese friend Hiro and I did some linked verse on a recent trip to Paris. What about these?

Bashō also used his hokku as crescendo points in short prose sketches and longer travel diaries, known as haibun (a combination of prose and haiku). His Oku no Hosomichi, or Narrow Road to the Deep North, is his magnum opus.

On my first return trip to Japan, I joined my friend Steph on something of a poetry pilgrimage, retracing some of Bashō’s route and finding the points at which certain poems were conceived. We wore pointy rice-farmer hats and got soaked in the rain. We wound ourselves up about the danger of bears and man-killing hornets. We plodded sombrely to the Fukushima exclusion zone. We got blisters.

I have myself conceived a notion that, on our upcoming trip to Japan, I might keep a Bashō-style haibun diary and post it here instead of the usual sort of post. Wide aeroplane to the Far East or something…?

Basho’s haiku. I love Basho’s haiku.