In light of today’s events, described below, I ought to be saying that I HATE the Rite of Spring. But in truth I love it, in all of its tonally-ambitious, rhythmically-stabbing, Pagan, filmic, accursed inglory.

This evening, I was walking home past the Angel pub in Islington - slightly scuzzy area. I had just finished listening to my listen-along Mandalorian podcast and, as the spring night’s dominion dimmed, on came the first movement of the Rite, L’Adoration de la Terre.

The haunting, alien bassoon, writhing, wailing around some obscure mode. Darkening London. The bassoon solo was taken from a Lithuanian folk song which Stravinsky presents in a variety of rhythms and ornamented with grace notes.

Of it, Stravinsky writes, “My idea was that the Prelude should represent the awakening of nature, the scratching, gnawing, wiggling of birds and beasts.”

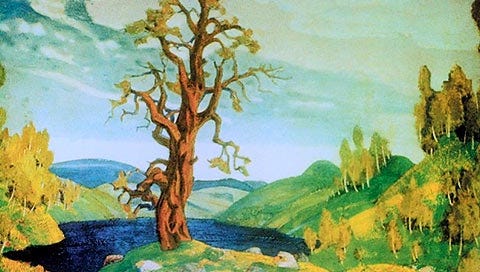

I had a fleeting vision which came to me as a complete surprise, my mind at the moment being full of other things. I saw in [my] imagination a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring. Such was the theme of the Sacre du Printemps. I must confess that this vision made a deep impression on me, and I at once described it to my friend, Nicholas Roerich, he being a painter who had specialised in pagan subjects. He welcomed my inspiration with enthusiasm, and became my collaborator in this creation.

You are transported to some grey-dust, golden Roerich landscape. Earth but not quite.

Indeed, I was so far transported that I did not realise my phone had been nicked, probably next to the scaffolding they’ve got up around Boots. I only realised then my earpods did the “phone too far away” noise and I started slapping my pockets and thighs to see what was going on.

What this thief deprived me of was about 35 minutes of “pound[ing] with the rhythm of engines, whirls and spirals like screws and fly-wheels, grinds and shrieks like laboring metal" (Paul Rosenfeld in 1920) or “great crunching, snarling chords from the brass and thundering thumps from the timpani” (Hesenfeld).

In 1907–08 Stravinsky set to music two poems from Sergey Gorodetsky's collection Yar. Another poem in the anthology, which Stravinsky did not set but is likely to have read, is Yarila: it contains many of the basic elements from which The Rite of Spring developed, including pagan rites, sage elders, and the propitiatory sacrifice of a young maiden.

If western music was ever tasteful, proportioned, balanced, the Sacré is by those standards profane. Like nature herself, I suppose, the Rite is characterised by the appearance of disorder, but a secret pattern beneath. The throbbing chords in the Augurs of Spring section are accented like this:

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

Then there are those eleven cataclysmic chords later on.

There is supposed to have been a riot at its first performance. Even if that might not be precisely true (I’ve been to the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées and it’s rather too arty for an affray), the Rite is certainly an energising work: contrast the Rite with other 1913 music - Holst’s jaunty tuneful St. Paul’s Suite (which I love):

Or Ravel’s shimmering languorous Daphnis et Chloe Suite (which I love):

But Stravinsky’s masterpiece is the true, knife-bearing breath of the Pagan spring. And the breath and seminus of modern music, ahead, perhaps, of its listening public.

The Rite of Spring. I love the Rite of Spring.